Without recourse. All Rights Reserved.

Tree of Life©

Statement of belief: “Sanctify them through

thy truth: thy word is truth.” (John

Created 5938[(??)] 01 25 2027

[2011-05-29]

Last edited 5938[(??)] 01 30 2027

[2011-06-02]

Revised Date Re

From the Ides of March to January 1…

That is, January 125 BCE, per the Roman Calendar then in use,

or, October 126 BCE per the Current used Julian Calendar…

&

Aemilius’ lunar eclipse at Numantia in

Abstract:

The conventionally accepted and proclaimed

year for

But when did this event really happen? What is

the closest secure anchor point in time for this event?

The best I’ve come up with thus far is a year

based upon the relative placement of the Consul Quintus Fulvius Nobilior, who

apparently was the incitement for this change of the Roman calendar, vs.

Sulpicius Gallus, which Sulpicius Gallus was Consul sometime after 139 BCE,

revised date, and who is listed in the conventional lists of Roman Consuls as

having been consul 13 years prior to Quintus Fulvius Nobilior. Given not only

that 13 year difference, but also the discovery, as here below outlined, that

Aemilius’ lunar eclipse at Numantine in Spain finds its best fit such that

Quintus Fulvius Nobilior’s consulship falls in 125 BCE, I conclude that Rome’s

calendar change, revised date, took place in 125 BCE, that is, 28 years later

than the conventional date…

Oooops, almost forgot… When exactly? If this move was decided upon in

January 125 BCE per the then current Roman calendar, well, things being what

they were in those days, that is, the calendar being about three months off

season, that is, three months ahead of our Julian calendar, this means that

this change was made in October 126 BCE!

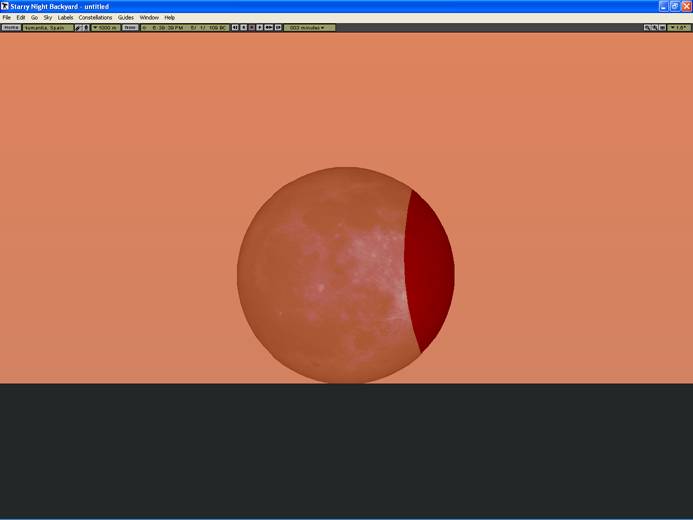

The waning partial eclipse of

May 1, 109 BCE as seen at moonrise over the Numantia, Spain horizon about ½ an hour

before sunset.

Quotes re Aemilius

Lepidus’ lunar eclipse:

“[§82] The siege of Pallantia was long protracted, the food supply of the

Romans failed, and they began to suffer from hunger. All their animals perished

and many of the men died of want. The

generals, Aemilius and Brutus, kept heart for a long time. Being compelled to

yield at last, they gave an order suddenly one night, about the last watch, to

retreat. The tribunes and centurions ran hither and thither to hasten the

movement, so as to get them all away before daylight. Such was the confusion

that they left behind everything, and even the sick and wounded, who clung to

them and besought them not to abandon them. Their retreat was

disorderly and confused and much like a flight, the Pallantines hanging on

their flanks and rear and doing great damage from early dawn till evening. When night came, the

Romans, worn with toil and hunger, threw themselves on the ground by companies

just as it happened, and the Pallantines,

moved by some divine

interposition, went back to their own country. And this was what

happened to Aemilius.“

(Appian’s History of Rome)

“Suffering from a lack of food, the Romans were compelled to retreat and

desperately tried to decamp under cover of darkness. "Such was the

confusion that they left behind everything, and even the sick and wounded, who

clung to them and besought them not to abandon them." Only a lunar eclipse saved the Romans from being

pursued. Lepidus was deprived of his command while still in the field (the

first time that such an abrogation ever had occurred) and recalled to

|

|

Comprehensive Listing of all (56) Lunar

Eclipses that may at all have been visible from |

|

|

|||||||

|

Legend: |

Legend: Re magnitude |

|

||||||||

|

No go |

Unlikely - minimal |

|

||||||||

|

Close |

Possible - partial |

|

||||||||

|

Likely |

Likely - total |

|

||||||||

|

# |

Date (Considering the events of the record, I find the most likely time to

be the fall, August and September. Unlikely, early calendar year, i.e. from

October or November through April.) |

Julian Year (BCE) |

Type of eclipse (Umbral magnitude) |

Time when eclipse became visible (Numantia, SNB local solar time) |

Numantia, UT time at maximum eclipse (Subtract: ‑10 minutes for local solar time) |

for Numantia (UT time) |

Comments & Considerations |

|||

|

1 |

June 1 |

139 |

Total |

|

|

|

All these eclipses should be at least ten

years too early… |

|||

|

2 |

November 26 |

139 |

Total |

|

|

|

||||

|

3 |

November 15 |

138 |

Partial (0.2881) |

|

|

|

||||

|

4 |

April 1 |

136 |

Partial (0.7227) |

|

|

|

||||

|

5 |

March 21 |

135 |

Total |

|

|

|

||||

|

6 |

September 14 |

135 |

Total |

|

|

|

||||

|

7 |

March 10 |

134 |

Partial (0.2510) |

|

|

|

||||

|

8 |

September 3 |

134 |

Partial (0.2402) |

Moonrise with 20% umbral eclipse |

|

|

||||

|

9 |

January 17 |

132 |

Total |

|

|

|

||||

|

10 |

January 7 |

131 |

Total |

|

|

|

||||

|

December 27 |

131 |

Partial (0.0281) |

|

|

|

|||||

|

12 |

May 12 |

129 |

Partial (0.5095) |

|

|

|

||||

|

13 |

November 5 |

129 |

Partial (0.6203) |

|

|

|

||||

|

14 |

May 2 |

128 |

Total |

|

|

|

||||

|

15 |

October 15 |

127 |

Partial (0.5171) |

|

|

|

||||

|

16 |

February 29 |

125 |

Partial (0.8114) |

|

|

|

||||

|

17 |

August 13 |

124 |

Total |

Fully eclipsed at moonrise, end of total eclipse at |

|

|

||||

|

18 |

February 7 |

123 |

Partial (0.2955) |

|

|

|

||||

|

19 |

August 2 |

123 |

Partial (0.1448) |

Moonrise with 8% umbral eclipse; umbral shadow ending at |

|

|

||||

|

20 |

June 12 |

121 |

Total |

|

|

|

||||

|

21 |

June 1 |

120 |

Total |

Penumbral eclipse |

|

|

||||

|

22 |

April 12 |

118 |

Partial (0.5908) |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

23 |

March 31 |

117 |

Total |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

24 |

September 24 |

117 |

Total |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

25 |

September 14 |

116 |

Partial (0.3023) |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

26 |

January 29 |

114 |

Total |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

27 |

January 18 |

113 |

Total |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

28 |

July 12 |

113 |

Total |

Penumbral eclipse 19:22-00:57; umbral eclipse 20:24-23:54; total eclipse

21:24-22:59 |

|

|

This month may well have been reckoned as

October, yet before the harvest season, though in the midst of the growing

season, it may seem a little bit questionable for the Roman army to be so

short of supply. |

|||

|

29 |

January 7 |

112 |

Partial (0.0398) |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

30 |

May 23 |

111 |

Partial (0.3692) |

Penumbral eclipse |

|

|

This month may well have been reckoned as August…

This being at the end of true winter, this seems like an excellent candidate… However, this eclipse onset may seem a bit

late to perfectly fit the recorded activities? |

|||

|

31 |

November 16 |

111 |

Partial (0.6172) |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

32 |

November 5 |

110 |

Total |

Moonrise at |

|

|

This month was likely reckoned as January or

February, thus not too likely… Yet possible? |

|||

|

33 |

May 1 |

109 [conventional 137 B.C.] |

Partial (0.5098) |

Moonrise at |

|

|

This month may well have been reckoned as August, late enough in the

Roman calendar year to allow for all the events on record… This being at the end of true winter, thus the shortness of supplies

and the famine… This seems like an excellent candidate, the best, indeed, fitting

perfectly also the distance in years of the Roman fasti, that is, the

record of the Roman Consuls, since the last prior identified eclipse,

Perseus’ eclipse at the Battle of Pydna in the year prior to the year when

Sulpicius Gallus and M. Claudius Marcellus were Consuls (conventional 166

B.C..) |

|||

|

34 |

October 25 |

109 |

Partial (0.5360) |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

35 |

March 11 |

107 |

Partial (0.7365) |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

36 |

September 4 |

107 |

Partial (0.7297) |

Moonrise at |

|

|

This month may well have been reckoned as December.

Yet, being in the harvest season it seems hard to believe that the Roman army

should be so short of supply. Too, this eclipse onset may seem a bit late

to perfectly fit the recorded activities? |

|||

|

37 |

February 28 |

106 |

Total |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

38 |

August 25 |

106 |

Total |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

39 |

August 13 |

105 |

Partial (0.2634) |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

40 |

December 28 |

104 |

Partial (0.8509) |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

41 |

December 17 |

103 |

Total |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

42 |

June 13 |

102 |

Total |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

43 |

December 6 |

102 |

Partial (0.3109) |

|

|

|

|

|||

|

44 |

October 16 |

100 |

Partial (0.7483) |

|

|

|

All these eclipses should be about ten years

too late for a god fit… |

|||

|

45 |

October 5 |

99 |

Total |

|

|

|

||||

|

46 |

March 31 |

98 |

Partial (0.4711) |

|

|

|

||||

|

47 |

August 3 |

96 |

Partial (0.7057) |

|

|

|

||||

|

48 |

January 29 |

95 |

Total |

|

|

|

||||

|

49 |

July 24 |

95 |

Total |

|

|

|

||||

|

50 |

July 13 |

94 |

Partial (0.2404) |

|

|

|

||||

|

51 |

June 3 |

93 |

Partial (0.2290) |

|

|

|

||||

|

52 |

November 26 |

93 |

Partial (0.6180) |

|

|

|

||||

|

53 |

May 23 |

92 |

Total |

|

|

|

||||

|

54 |

November 16 |

92 |

Total |

|

|

|

||||

|

55 |

May 13 |

91 |

Partial (0.6580) |

|

|

|

||||

|

56 |

November 5 |

91 |

Partial (0.5481) |

|

|

|

||||

|

Roman Consuls [used

here as a tool for estimating the difference in time between

Perseus’ eclipse in 139 BCE, and Consul Aemilius’ eclipse] [Excerpt

from Ancient / Classical History; Revised

Julian year BCE column, all emphasis, and all brackets added] |

||||

|

Names and dates of the consuls of including dictators, suffect consuls and military

tribunes with consular power. |

||||

|

Revised Julian year BCE |

Year B.C. |

Consul one |

Consul two |

|

|

? |

206 |

Q. Caecilius Metellus |

L. Veturius Philo |

|

|

? |

205 |

P. Cornelius

Scipio Africanus I |

P.Licinius Crassus |

|

|

? |

204 |

M. Cornelius Cethegus |

P. Sempronius Tuditanus |

|

|

? |

203 |

C. Servilius Geminus |

Cn. Servilius Caepio |

|

|

190 |

202 [Revised date for Please cf. this

link for details! / ToL] |

Ti. Claudius Nero |

M. Servilius Geminus |

|

|

? |

201 |

Cn. Cornelius Lentulus |

P. Aelius Paetus |

|

|

? |

200 |

P. Sulpicius Galba II |

C. Aurelius Cotta |

|

|

? |

199 |

L. Cornelius Lentulus |

P. Villius Tappulus |

|

|

? |

198 |

T. Quinctius Flaminius |

Sextus Aelius Paetus |

|

|

? |

197 |

C. Cornelius Cethegus |

Q. Minucius Rufus |

|

|

? |

196 |

L. Furius Purpurio |

M. Claudius Marcellus |

|

|

? |

195 |

L. Valerius Flaccus |

M. Porcius Cato |

|

|

? |

194 |

P. Cornelius Scipio Africanus II |

Ti. Sempronius Longus |

|

|

? |

193 |

L. Cornelius Merula |

Q. Minucius Thermus |

|

|

? |

192 |

L. Quinctius Flaminius |

Cn. Domitius Ahenobarbus |

|

|

? |

191 |

P. Cornelius Scipio Nasica |

Manius Acilius Glabrio |

|

|

? |

190 |

L. Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus |

C. Laelius |

|

|

? |

189 |

Cn. Manlius Vulso |

M. Fulvius Nobilior |

|

|

? |

188 |

M. Valerius Messalla |

C. Livius Salinator |

|

|

? |

187 |

M. Aemilius Lepidus I |

C. Flaminius |

|

|

? |

186 |

Sp. Postumius Albinus |

Q. Marcius Philippus I |

|

|

? |

185 |

App. Claudius Pulcher |

M. Sempronius Tuditanus |

|

|

? |

184 |

P. Claudius Pulcher |

L. Porcius Licinius |

|

|

? |

183 |

Q. Fabius Labeo |

M. Claudius Marcellus |

|

|

? |

182 |

L. Aemilius Paullus I |

Cn. Baebius Tamphilus |

|

|

? |

|

Suffect consul |

|

|

|

? |

[1st Celtiberian War begins?] |

Q. Fulvius Flaccus |

|

|

|

? |

181 |

P. Cornelius Cethegus |

M. Baebius Tamphilus |

|

|

? |

180 |

A. Postumius Albinus |

C. Calpurnius Piso |

|

|

? |

179 [1st Celtiberian War begins?] |

L. Manlius Acidinus |

Q. Fulvius Flaccus |

|

|

? |

178 |

A. Manlius Vulso |

M. Junius Brutus |

|

|

? |

177 |

C. Claudius Pulcher |

Ti. Sempronius Gracchus I |

|

|

? |

177 |

C. Claudius Pulcher |

Ti. Sempronius Gracchus I |

|

|

? |

176 |

Cn. Cornelius Scipio Hispallus |

Q. Petillius Spurinus |

|

|

? |

175 |

M. Aemilius Lepidus II |

P. Mucius Scaevola |

|

|

? |

174 |

Sp. Postumius Albinus |

Q. Mucius Scaevola |

|

|

? |

173 |

L. Postumius Albinus |

M. Popillius Laenas |

|

|

? |

172 |

P. Aelius Ligus |

C. Popillius Laenas I |

|

|

? |

171 |

C. Cassius Longinus |

P. Licinius Crassus |

|

|

? |

170 |

A. Atilius Serranus |

A. Hostilius Mancinus |

|

|

? |

169 |

Cn. Servilius Caepio |

Q. Marcius Philippus II |

|

|

? |

168 |

L. Aemilius Paullus II |

C. Licinius Crassus |

|

|

139 |

167 [Revised date for the and Perseus’ lunar eclipse: Please cf. this

link for details! / ToL] |

Q. Aelius Paetus |

M. Junius Pennus |

|

|

138 |

166 |

C. Sulpicius

Galba [C. Sulpicius Galus; cf. Early Roman Chronology, or cf. Andraeus

Papadopolus] |

M. Claudius Marcellus I |

|

|

137 |

165 |

T. Manlius Torquatus |

Cn. Octavius |

|

|

136 |

164 |

A. Manlius Torquatus |

Q. Cassius Longinus |

|

|

135 |

163 |

Ti. Sempronius Gracchus II |

M. JuventiusThalna |

|

|

134 |

162 |

P. Cornelius Scipio Nasica Corculum I |

C.Marcius Figulus I |

|

|

|

|

Suffect consul |

|

|

|

|

|

P. Cornelius Lentulus |

Cn. Domitius Ahenobarbus |

|

|

133 |

161 |

M. Valerius Messalla |

C. Fannius Strabo |

|

|

132 |

160 |

M. Cornelius Cethegus |

L. Anicius Gallus |

|

|

131 |

159 |

Cn. Cornelius Dolabella |

M. Fulvius Nobilior |

|

|

130 |

158 |

M. Aemilius Lepidus |

C. Popillius Laenas II |

|

|

129 |

157 |

Sextus Julius Caesar |

L. Aurelius Orestes |

|

|

128 |

156 |

L. Cornelius Lentulus Lupus |

C. Marcius Figulus II |

|

|

127 |

155 |

P. Cornelius Scipio Nasica Corculum II |

M. Claudius Marcellus II |

|

|

126 |

154 |

L. Postumius Albinus |

Q. Opimius |

|

|

125 |

153 [2nd Celtiberian War begins] |

T. Annius Luscus |

Q. Fulvius Nobilior |

|

|

124 |

152 |

L. Valerius Flaccus |

M. Claudius Marcellus III |

|

|

123 |

151 [Lucullus’ Raid] |

A.

Postumius Albinus |

L. Licinius Lucullus |

|

|

122 |

150 |

T. Quinctius Flaminius |

Manius Acilius Balbus |

|

|

121 |

149 |

Manius Manilius |

L. Marcius Censorinus |

|

|

120 |

148 |

Sp. Postumius Albinus Magnus |

L. Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus |

|

|

119 |

147 |

P. Cornelius Scipio Africanus Aemilianus I |

C. Livius Drusus |

|

|

118 |

146 [The

War of Fire – Viriathus’ 8 yr War begins] |

Cn. Cornelius Lentulus |

L. Mummius Achaicus |

|

|

117 |

145 |

Q. Fabius Maximus Aemilianus |

L. Hostilius Mancinus |

|

|

116 |

144 |

Ser. Sulpicius Galba |

L. Aurelius Cotta |

|

|

115 |

143 [The Numantine War begins] |

App. Claudius Pulcher |

Q. Caecilius Metellus Macedonicus |

|

|

114 |

142 |

Q. Fabius Maximus Servilianus |

L. Caecilius Metellus Calvus |

|

|

113 |

141 |

Cn. Servilius Caepio |

Q. Pompeius |

|

|

112 |

140 |

Q. Servilius Caepio |

C. Laelius Sapiens |

|

|

111 |

139 |

Cn. Calpurnius Piso |

M. Popillius Laenas |

|

|

110 |

138 |

P. Cornelius Scipio Nasica Serapio |

D. Junius Brutus Callaicus |

|

|

109 |

137 [The year of

the of Consul

Aemilius] |

M. Aemilius Lepidus Porcina |

C. Hostilius Mancinus |

|

|

? |

136 |

L. Furius Philus |

Sextus Atilius Serranus |

|

|

? |

135 |

Q. Calpurnius Piso |

Ser. Fulvius Flaccus |

|

|

? |

134 |

C. Fulvius Flaccus |

P. Cornelius

Scipio Africanus Aemilianus II |

|

|

? |

133 |

L. Calpurnius Piso Frugi |

P. Mucius Scaevola |

|

|

? |

132 |

P. Popillius Laenas |

P. Rupilius |

|

Pertinent Quotes:

The Roman Calendar

Nor did the college of pontiffs (from pontifex or "bridge

maker"), who were responsible for regulating the calendar and the festivals

that depended upon it, always intercalate the additional days necessary to

synchronize the lunar and solar years. Intercalation was considered unlucky

and, during the Second Punic War (218-201 BC), when

With the expulsion of Tarquinius Superbus, the last Etruscan king, and

the establishment of the

Why the consular year began on January 1 was due to the Second Celtiberian War. In 154 BC, there was rebellion in

The Celtiberian War

Scipio Africanus had wrested

There had been peace for almost a

quarter of a century when, in 155 BC, a raid into Hispania Ulterior (Farther

Spain) by the Lusitani and the defeat of

two successive Roman praetors encouraged the town of

(Nobilior had been designated consul for the following year but could

not assume office until the Ides of March. Given the military situation, the

Senate decreed January 1 to be the start of the new civil year, which permitted

him to depart with his legions that much sooner. His defeat on August 23 was so

disastrous that the day on which it occurred was declared a dies aster and

subsequently considered unlucky. Indeed, Appian relates that no Roman general

would willingly initiate a battle on that day.)

The Third

Celtiberian War…

Hostilius

Mancinus, the next consul, fared no better. In 137 BC, while besieging Numantia (Numancia), he panicked at the rumor that

reinforcements were being sent and surrendered his entire army, pledging peace

between

Quotes with time

references from Appian’s History of Rome:

[§38]

[205] From this time, which was a little

before the 144th Olympiad, [207 BCE / ToL] the Romans began to send praetors to Spain

yearly to the conquered nations as governors or superintendents to keep the

peace. Scipio left them a small force suitable for a peace establishment, and

settled his sick and wounded soldiers in a town which he named Italica after

[§42]

[181] Four Olympiads later [147th or 148th ?

195 BCE or 191 BCE / ToL] -that is,

about the 150th Olympiad [183 BCE / ToL]- many Spanish tribes, having insufficient

land, including the Lusones and others who dwelt along the river Iberus,

revolted from the Roman rule. These being overcome in battle by the consul [Quintus]

Fulvius Flaccus [182 BCE conventional, but 16 yrs before Gallus and

Marcellus, that is, 16 yrs before 139 BCE (=155 BCE)… OR ELSE Q. Fulvius

Flaccus IIII of 209 BC conventional, 10 yrs before 190 BCE revised, that is,

about 200 BCE? This seems to agree best with the 147th Olympiad in 195 BCE?? /

ToL], the greater part of them scattered among their towns.

[§43] [179] Flaccus was succeeded in the command by Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus… [163

conventional, but 3 years after Gallus and Marcellus of 139 BCE revised, that

is, 136 BCE… OR ELSE 215, 213, or 177 BC conventional]

[§44]

[154] Some years later another serious

war broke out in

[§45] [153] Accordingly the praetor

[Quintus Fulvius] Nobilior [MFN 189, 159 BC?? Or QFN 153? conventional] was

sent against them with an army of nearly 30,000 men…. This disaster happened on

the day on which the Romans are accustomed to celebrate the festival of Vulcan [

[§47] Nobilior, recovering a little from this disaster, made an attack

upon the stores which the enemy had collected at the town of

[§48] [152] The

following year [Marcus] Claudius Marcellus succeeded Nobilior in the command…

[§49] Marcellus sent ambassadors from each party to

[§50] [151] While Lucullus was on the march Marcellus notified the

Celtiberians of the coming war… Thus the war with the Belli, the Titthi, and

the Arevaci was brought to an end before Lucullus arrived.

[§51]

[151] [The consul Lucius Licinius]

Lucullus being greedy of fame and needing money, because he was in

straitened circumstances, invaded the territory of the Vaccaei, another

Celtiberian tribe, neighbors of the Arevaci, against whom war had not been

declared by the Senate,

nor had they ever attacked the Romans, or offended Lucullus himself.

[§55] … Lucullus passed into the territory of the Turditani, and went

into winter quarters. This was the end

of the war with the Vaccaei, which was waged by Lucullus without the authority

of the Roman people, but he was never called to account for it…

[§56]

[155] At this time another part of

autonomous Spain called Lusitania, under Punicus as leader, was ravaging the

fields of the Roman subjects and having put to flight their praetors (first

Manilius and then Calpurnius Piso), killed 6,000 Romans and among them

Terentius Varro, the quaestor.

[153] He was succeeded by a man named Caesarus. The latter joined battle

with [the praetor Lucius] Mummius,

who came from

[§58] [152] He was succeeded in

the command by Marcus Atilius…

[151] Servius [Sulpicius]

Galba, the successor of Atilius, hastened to relieve them…

[§59] [151/150] [The

consul Lucius Licinius] Lucullus, who had made war on the Vaccaei without

authority, was wintering in Turditania…

[Note re timing: After Lucius

Licinius Lucullus (conv. 151 BC) - Quintus Servilius Caepio (conv. 140 BC) = “8

years” / ToL]

[§61]

[147] Not long afterward those

[Lusitanians] who had escaped the villainy of [consul Lucius Licinius] Lucullus and [praetor Servius Sulpicius] Galba…

[§62] Excited by the new hopes with which he inspired them, they chose

him as their leader. He drew them up in line of battle as though he intended to

fight, but gave them orders that when he should mount his horse they should

scatter in every direction and make their way by different routes to the city

of Tribola and there wait for him. He chose 1,000 only whom he commanded to

stay with him. These arrangements having been made, they all fled as soon as

Viriathus mounted his horse, Vetilius was afraid to pursue those who had

scattered in so many different ways, but turning towards Viriathus who was

standing there and apparently waiting a chance to attack, joined battle with

him. The latter, having very swift horses, harassed the Romans by attacking,

then retreating, again standing still and again attacking, and thus consumed

the whole of that day and the next dashing around on the same field. As soon as

he conjectured that the others had made good their escape, he hastened away in

the night by devious paths and arrived at Tribola with his nimble steeds, the

Romans not being able to follow him at an equal pace by reason of the weight of

their armor, their ignorance of the roads, and the inferiority of their horses.

Thus did Viriathus, in an unexpected way, rescue his army from a desperate

situation. This feat, coming to the knowledge of the various tribes of that

vicinity, brought him fame and many reinforcements from different quarters, and

enabled him to wage war against the Romans for eight years.

[§64] [146] Viriathus overran the fruitful country of Carpetania without

hindrance, and ravaged it until Gaius

Plautius came from

[§65] [145] When these facts became known at

[144] Winter being ended, and his army well disciplined, he attacked

Viriathus and was the second Roman general to put him to flight (although he

fought valiantly), capturing two of his cities, one of which he plundered and

the other burned. He pursued Viriathus to a place called Baecor, and killed

many of his men, after which he wintered at Corduba.

[§66] [143] Now Viriathus, being not so confident as before, detached

the Arevaci, Titthi, and Belli, very warlike peoples, from their allegiance to

the Romans, and these began to wage another war on their own account which was

long and tedious to the Romans, and which was called the Numantine war from one

of their cities. I shall give an account of this after finishing the war with

Viriathus.

The latter coming to an engagement in another part of

[§67] At the end of the

year, [consul Quintus] Fabius Maximus Servilianus, the brother of Aemilianus,

came to succeed Quintus in the command, bringing two new legions from

[§68]… Then he went

into winter quarters, having already been two years in the command. Having performed

these labors, Servilianus returned to

[Note re timing: Conv. 143 –

134 BC]

[§76]

[143] Our history returns to the war against the Arevaci and the Numantines,

whom Viriathus stirred up to revolt. [Consul Quintus] Caecilius Metellus was sent against them from

[142 or 141] At the

end of winter Metellus surrendered to his successor, Quintus Pompeius Aulus, the command of the army, consisting of 30,000 foot

and 2,000 horse, admirably trained. While encamped against Numantia, Pompeius

had occasion to go away somewhere. The Numantines made a sally against a body

of his horse that was ranging after him and destroyed them. When he returned,

he drew up his army in the plain. The Numantines came down to meet him, but

retired slowly as though intending flight, until they had drawn Pompeius to the

ditches and palisades.

[§79] Pompeius, being cast down by so many misfortunes, marched away

with his senatorial council to the towns to spend the rest of the winter, expecting a successor to

come early in the spring. Fearing lest he should be called to account, he made

overtures to the Numantines secretly for the purpose of bringing the war to an

end. The Numantines themselves, being exhausted by the slaughter of so many of

their bravest men, by the loss of their crops, by want of food, and by the

length of the war, which had been protracted beyond expectation, sent legates

to Pompeius. He publicly advised them to surrender at discretion, because no

other kind of treaty seemed worthy of the dignity of the Roman people, but

privately he told them what terms he should impose. When they had come to an

agreement and the Numantines had given themselves up, he demanded and received

from them hostages, together with the prisoners and deserters. He also demanded

thirty talents of silver, a part of which they paid down and the rest he agreed

to wait for.

[139] His successor,

Marcus Popillius Laenas, had arrived when they brought the last instalment…

[§80]… When these things were known at

[§82] The siege of Pallantia was long protracted, the food supply of the Romans failed, and they began to

suffer from hunger. All their

animals perished and many of the men died of want. The generals, Aemilius and

Brutus, kept heart for a long time. Being compelled to yield at last, they gave an order suddenly

one night, about the last watch, to retreat.

The tribunes and centurions ran hither and thither to hasten the movement, so

as to get them all away before daylight. Such was the confusion that they left behind

everything, and even the sick and wounded, who clung to them and besought them

not to abandon them. Their retreat was disorderly and confused and much like a

flight, the Pallantines hanging on their

flanks and rear and doing great damage from early dawn till evening.

When night came, the Romans, worn with

toil and hunger, threw themselves on the ground by companies just as it

happened, and the Pallantines, moved by some divine interposition, went back to their own country. And this was what

happened to Aemilius.

[§83] When these things were known at

[135] [Quintus] Calpurnius

Piso

was chosen general against them, but he did not march against Numantia. He made

an incursion into the

[§84] [134] The Roman people being tired of this Numantine war, which

was protracted and severe beyond expectation, elected [Publius Cornelius] Scipio [Aemilianus], the conqueror of

Carthage, consul again, believing that he was the only man who could subdue

the Numantines. As he was still under the consular age, the Senate voted, as

was done when Scipio was appointed general against the Carthaginians, that the

tribunes of the people should repeal the law respecting the age limit, and

reenact it for the following year. Thus Scipio was made consul a second time

and hastened to Numantia.

Later conflicts

[§99]

The Romans, according to their custom, sent ten senators to the newly acquired

provinces of

At a later time, other revolts having taken place in

[§100] There was another city near Colenda inhabited by mixed tribes of

Celtiberians who had been the allies of Marcus Marius in a war against the

Lusitanians, and whom he had settled

there five years before with the approval of the Senate. They were living

by robbery on account of their poverty. Didius, with the concurrence of the ten

legates who were still present, resolved to destroy them. Accordingly, he told

their principal men that he would allot the

(Appian’s History of Rome)

Comments and donations freely

accepted at:

Tree of Life©

c/o General Delivery

Nora [near SE-713 01]

eMail: TreeOfLifeTime@gmail.com

…

…

The GateWays

into Tree of Life Chronology Forums©

The

GateWays of Entry into the Tree of Life Time Chronology Touching upon the Book

of Daniel©

Pearls

& Mannah – “I found it!”

Feel free to use,

and for sharing freely with others, any of the truth and blessings belonging to

God alone. I retain all the copyrights to the within, such that no one may

lawfully restrain my use and my sharing of it with others. Including also all

the errors that remain. Please let only me know about those. I need to know in

order to correct them. Others don’t need to be focused upon the errors that

belong to me alone. Please respect that, and please do not hesitate to let me

know of any certain error that you find!

Without recourse.

All Rights Reserved. Tree of Life©