Without recourse. All

Rights Reserved. Tree of Life©

Statement

of belief: “Sanctify them through thy truth: thy word is truth.” (John

Created 5941[(?)] 10 29 2027

[2011-02-03]

Last edited 5938[(??)] 01 25 2027 [2011-05-29]

Revising

ancient Greek history by 30 years…

Pericles’

solar eclipse

at

the end of the 1st year of the Peloponnesian War

took

place

at

about

&

The

Lunar Eclipse of the

took

place on

between

Abstract:

A close study of the NASA Canon of Eclipses,

in conjunction with the use of currently available astronomy software, and in

comparison with the primary historical records makes it quite clear that the

total solar eclipse of

This finding goes hand in hand with a revised

date also for the total lunar eclipse of the battle of

Thus, both of these events agree with one

another in moving the conventionally accepted dates for these anchor points of

Greek history about 30 years closer to our own time in comparison to that which

has been heretofore commonly taught and believed.

Praise the Lord of Hosts, the Yahweh Elohim

who alone is the One who knows all truth, for teaching and showing me all these

wonderful things!

Considerations:

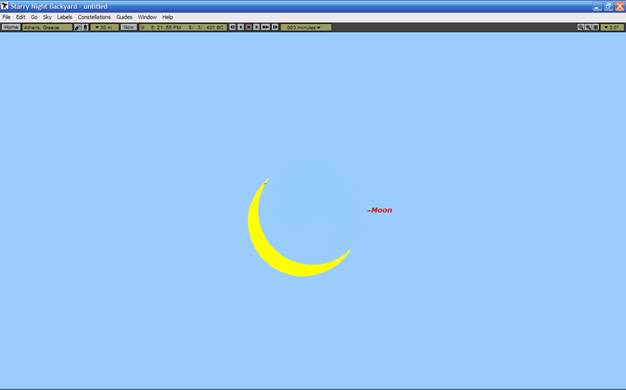

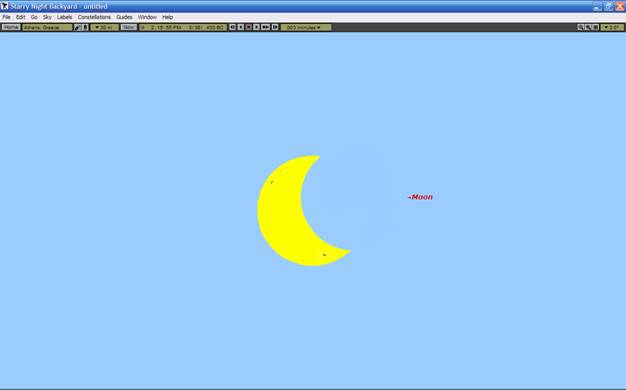

Using NASA’s Five Millennium Canon of Eclipses

and my Starry Night Backyard software

for carefully reviewing all (partial, total, annular, and hybrid) solar

eclipses for 100+ years both ways[1]

from 432 BCE and the conventionally accepted timing of the Peloponnesian war, I

find only one solar eclipse that satisfies 1) Plutarch’s words “the

sun was eclipsed and darkness came on,” and 2) the corresponding

record of Thucydides (cf. this link!) Unfortunately

for those who tend to rely on the conventional consensus of the majority among

themselves, this one solution is not anywhere near supporting the conventional

belief re the timing of that war. The eclipse I am referencing is the total

eclipse that occurred on

Now at first sight that date, “January 18,”

might seem to be at odds with the records of Plutarch (“ca 46-120 CE”) and

Thucydides (“c. 460 BC – c. 395 BC,) that is, words such as “In the very beginning of summer,” but let’s dive

into the details and I believe that I may well be able to convince the sharpest

among you, my dear readers, that this date, January 18, 402 BCE, exactly fits

the record. Please bear with me just a little!

First, comparing Plutarch’s and Thucydides’

records, I find it clear from Plutarch’s The Life of Pericles (authored c. 500

years after the fact!) that the solar eclipse event that he (Plutarch)

describes is associated with these three identifying characteristics:

1) Pericles “manned a hundred and fifty ships of war…”

against the

2) then comes a very specific action: The “laying siege to sacred Epidaurus…,”

and

3) “a pestilential destruction fell upon them,”

which was more or less concurrent with a certain forty day period of time

referenced by Thucydides, who lived and worked at the very time of these

events, which events he was indeed even a part of.

Finding these very same events being described

by very similar language by Thucydides in his History of the Peloponnesian

War…:

1) Pericles “he furnished a hundred galleys to go about

Peloponnesus and… The Chians and Lesbians joined… with fifty galleys.…”

against the

2) then the same specific action: “Coming before Epidaurus, a city of Peloponnesus, they

wasted much of the country thereabout and assaulting the city had a hope to

take it…,” and

3) “They had not been many days in Attica when the plague

first began amongst the Athenians,” which plague

was more or less concurrent with that certain forty day period of time

referenced by Thucydides, who lived and worked at the very time of these

events, which events he was indeed even a part of.

It is quite clear to me that Plutarch’s and

Thucydides’ stories are complementary to one another in these particulars, such

that where Plutarch’s record provides less detail as to the events and their

relative timing in terms of for instance “winter” and “summer,” he, Plutarch,

is the only an apparently distinct and separate record of a distinct and

separate observation of this solar eclipse, which solar eclipse is in itself a

unique and exceedingly exact and reliable time stamp, that is, considering all

the astronomical facts of the matter inherent in Plutarch’s words “the sun was eclipsed and

darkness came on” as well as in Thucydides’ words “in the afternoon happened

an eclipse of the sun. The which, after it had appeared in the form of a

crescent and withal some stars had been discerned.” Given the above

said three unique identifiers, Thucydides’ records help us further with the

timing of this event by adding the following sequence of words, which words

must certainly be given precedence over and above any ambiguity of Plutarch’s

record:

“47.… In the

very beginning of summer the

Peloponnesians and their confederates… invaded

“49. This year…

“55…

[2] And Pericles, who was also then general…

“56… furnished a hundred galleys to go about

“57.

All the while the Peloponnesians were in the territory of the Athenians and the

Athenians abroad with their fleet, the sickness, both in the army and city,

destroyed many, insomuch as it was said that the Peloponnesians, fearing the

sickness (which they knew to be in the city both by fugitives and by seeing the

Athenians burying their dead), went the sooner away out of the country. [2] And

yet they stayed there longer in this invasion than they had done anytime before

and wasted even the whole territory, for they

continued in

“58. The same summer…

“66.

The Lacedaemonians and their confederates made war the

same summer with one hundred galleys against

Zacynthus…

“67. In the end of the same summer…

“68. About the same time, in the end of summer… These were the

acts of the summer.

“69. In the beginning of the winter the Athenians sent twenty

galleys about

“70. The same winter… These were the things done in this winter.

And so ended the second year of this war, written by Thucydides.

“71. The next summer…”

Looking carefully at the details of the above

quoted passages of Thucydides, it is obvious that Pericles and his 150 ships

and the associated solar eclipse darkness took place within, or before, the

forty days following “the very beginning of summer.”

Indeed, I do not see much if any evidence of there being a problem with the

plague among those who left with Pericles on the ships, and thus they too seem

to have left very close to “the very beginning of summer…”

and before “not… many days… when the plague first began amongst the Athenians…”

Yes, it is true that Thucydides is describing the plague prior to Pericles leaving with the ships,

but he is not using express words to the effect that that was the order of

events. One might also wish to consider whether or not plagues generally are

not a phenomenon of the [real time] mid-winter season? Considering also the accusations against Pericles

that began while the city was being attacked, how likely would Pericles be to

leave with the ships at such a time, which indeed he had not done at the

time of sending the ships off on the prior year’s crusade?

Also, it seems quite certain that his second speech was a

remedy against said accusations which speech he engineered at the time of his

return with the fleet following the raid of this second summer of the war.

Where is Paralos? Is it a variant name for Paralia, or not? Lastly, considering

carefully the language of the following two passages, I find said order of events

confirmed. That is, Pericles and his fleet left prior to the invasion of

2.55. After the

Peloponnesians had wasted the champaign country, they fell upon the territory

called Paralos

as far as to the mountain Laurius where the Athenians had silver mines, and

first wasted that part of it which looketh towards

2.56. Whilst they [the Peloponnesians/ToL]

were yet in the plain and before they [the Peloponnesians/ToL] entered

into the maritime country [= “before the P. set out to sea?,” /ToL] he [Pericles/ToL] furnished a hundred galleys to go about

Which “Paralia,”

which ‘beach,’ is here being referenced?

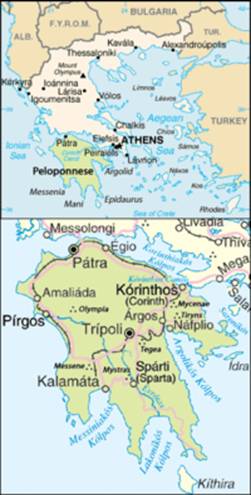

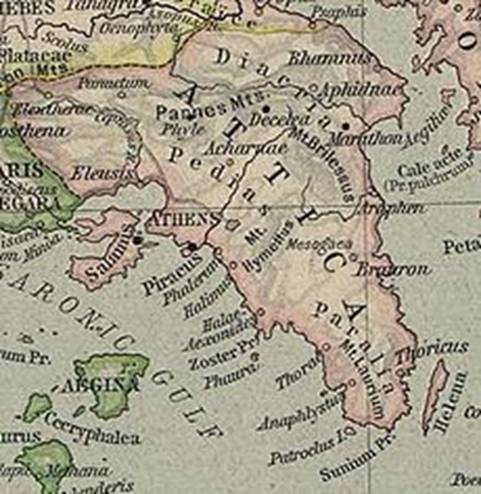

Cf. the maps below and the location of at least nine (9) different places in

Perhaps 2.47 is better placed subsequent to

2.56?:

2.47.… In the very

beginning of summer the

Peloponnesians and their confederates… invaded

Map of ancient

Re the W. T. Lynn’s argument

re many events…:

It seems to me that W.T. Lynn is mixing up the

1st and the 2nd raids of Pericles into

At any rate, the popularly supported annular

eclipse of

The

maximum eclipse as seen from

The

maximum eclipse as seen from

The solution to the apparent

paradox

re a January 18 conjunction vs.

Thucydides’ words “In the very beginning of summer…”

Now, here’s the tricky part, that is, to the

extent that the above said is not in and of itself sufficiently convincing: How

can a solar eclipse that occurred on January 18 be associated with an event

within “almost forty days…” following “the very beginning of summer?” That does

seem contradictory, does it not? However, consider these facts: The only two

seasons referenced by Thucydides are winter and summer. Given that, in terms of

our modern calendars, the beginning of summer is the beginning of April (the

2nd quarter of the year; which at the time of the beginnings of both the Greek

and the Roman Calendars was concurrent with the spring equinox,) and that the

beginning of winter is the beginning of October (the 4th quarter of the year;

initially the fall equinox,) we may conclude that, per the calendars then in

use, the time referenced by the words “in the very beginning of summer” more

than likely are words tied to their then current official calendar year, while

not necessarily being words tied to the actual seasons of the year (or to the

solstices; cf. the Egyptian calendar where Thoth 1, the 1st day of the Egyptian

year, began December 2, 402 BCE.) More than likely then, Plutarch’s words “ the

very beginning of summer” reference a point in time no later than the first day

of Artemisios, the lunar month which typically begins in April [cf.

Strong’s G736 “(something hung up), that is, (specifically) the topsail

(rather foresail or jib) of a vessel,”] but very possibly even

the first day of Xanthikos [cf. Strong’s G1816 “to start up out

of the ground, that is germinate,”] the month usually associated with

the spring equinox these days, that is, Xanthikos typically begins in

March and these days we associate the spring equinox with March 21, but that

was not always so!

Re Xanthikos vs. the beginning of the

year: Consider these words:

“Originally the Romans

reckoned March as the first month of the year; the decision to begin the year

on January 1 did not come until 153 BCE…”

(From Svensk Uppslagsbok (1956,) Vol. 16, ‘Kronologi:

Column 1249;’(my translation.) The original Swedish words are: “Romarna urspr.

betraktade mars som årets första mån.; först 153 f.Kr. bestämdes årets början

till 1 jan..”)

Re Caesar Julius’ calendar revision,

and re the eclipse at the battle of Pydna

However, as we know, Caesar Julius is commonly

associated with a very revolutionary calendar correction due to the drifting of

the seasons up until that time. I believe this is based most firmly upon Suetonius’

words per The Life of Julius Caesar (Chapter 40,) albeit

having been falsely associated with the

“16… 4 After

this disaster, Perseus

hastily broke camp and retired; he had become exceedingly fearful, and his

hopes were shattered. 5 But nevertheless he was under the necessity of

standing his ground there in front of Pydna and

risking a battle, or else of scattering his army about among the cities and so

awaiting the issue of the war, which, now that it had once made its way into

his country, could not be driven out without much bloodshed and slaughter. 6 In

the number of his men, then, he was superior where he was, and they would fight

with great ardour in defence of their wives and children, and with their king

beholding all their actions and risking life in their behalf. 7 With such

arguments his friends encouraged Perseus. So he pitched a camp and arranged his

forces for battle, examining the field and distributing his commands, purposing

to confront the Romans as soon as they came up. 8 The place afforded a

plain for his phalanx, which required firm standing and smooth ground, and

there were hills succeeding one another continuously, which gave his

skirmishers and light-armed troops opportunity for retreat and flank attack.

9 Moreover, through the middle of it ran the rivers Aeson and Leucus, which

were not very deep at that time (for it was the latter end of summer),

but were likely, nevertheless, to give the Romans considerable trouble.”

“17… 7 Now,

when night had come, and the soldiers, after supper, were betaking themselves

to rest and sleep, on a sudden the moon, which was full and high in the

heavens, grew dark, lost its light, took on all sorts of colours in succession,

and finally disappeared.

“8 The

Romans, according to their custom, tried to call her

light back by the clashing of bronze utensils and by holding up many blazing

fire-brands and torches towards the heavens; the

Macedonians, however, did nothing of this sort, but amazement and terror

possessed their camp, and a rumor quietly spread among many of them that the

portent signified an eclipse of a king. 9 Now, Aemilius was not altogether

without knowledge and experiences of the irregularities of eclipses, which, at

fixed periods, carry the moon in her course into the shadow of the earth and conceal her from sight, until she passes beyond the region of shadow

and reflects again the light of the sun; 10 however, since he was very

devout and given to sacrifices and divination, as

soon as he saw the moon beginning to emerge from the shadow, he sacrificed

eleven heifers to her…”

Plutarch, The Life of Aemilius 17.7

“The reason verily of both eclipses, the first Romane

that published abroad and divulged, was Sulpitius Gallus, who

afterwards was Consul, together with M. Marcellus: but at that time being a Colonell, the day before that king Perseus was vanquished by

Paulus, he was brought

forth by the Generall into open audience before the whole hoast, to fore-tell the eclipse which should happen the next

morrow: whereby he

delivered the armie from all pensivenesse and fear, which might have troubled

them in the time of battaile, and within a while after hee compiled also a

booke thereof. But among the Greekes, Thales Milosius was the first that found

it out, who in the 48 Olympias, and the fourth yeere thereof, did prognosticate

and foreshew the Sunnes eclipse that happened in the raigne of Halyattes, and

in the 170 yeere after the foundation of the citie of

C. Plinvs

Secvndvs, The Second

Booke of the Historie of Natvre, Chap. VII

“[37] Paulus postquam metata castra impedimentaque conlocata

animaduertit, ex postrema acie triarios primos subducit, deinde principes,

stantibus in prima acie hastatis, si quid hostis moueret, postremo hastatos, ab

dextro primum cornu singulorum paulatim signorum milites subtrahens. ita

pedites equitibus cum leui armatura ante aciem hosti oppositis sine tumultu

abducti, nec ante, quam prima frons ualli ac fossa perducta est, ex statione

equites reuocati sunt. rex quoque, cum sine detractatione paratus pugnare eo

die fuisset, contentus eo, quod per hostem moram fuisse scirent, et ipse in

castra copias reduxit.

Castris

permunitis C. Sulpicius Gallus, tribunus militum secundae legionis,

qui praetor superiore anno fuerat, consulis permissu ad contionem militibus

uocatis pronuntiauit, nocte proxima, ne quis id pro

portento acciperet, ab hora secunda usque ad quartam horam noctis lunam

defecturam esse. id quia

naturali ordine statis temporibus fiat, et sciri ante et praedici posse. itaque

quem ad modum, quia certi solis lunaeque et ortus et occasus sint, nunc pleno

orbe, nunc senescentem exiguo cornu fulgere lunam non mirarentur, ita ne

obscurari quidem, cum condatur umbra terrae, trahere in prodigium debere. nocte, quam pridie nonas Septembres insecuta est dies, edita hora luna cum defecisset, Romanis militibus Galli sapientia

prope diuina uideri; Macedonas ut triste prodigium, occasum regni perniciemque

gentis portendens, mouit nec aliter uates. clamor ululatusque in castris

Macedonum fuit, donec luna in suam lucem emersit.”

Notice that, per the Latin quote above, this

lunar eclipse took place on the 4th of September, as reckoned by the

Roman calendar of that time, and that the eclipse began in the 1st

quarter of the 2nd hour of night. Given that the local solar time of

sunset, at Pydna at the evening of this particular eclipse, June 1, 139 BCE,

was 7:16 PM[2],

I find that the 2nd hour of night began at 8:16 PM and that the

first quarter of that hour ended at 8:31 PM, and that this is a perfect fit for

the onset of the penumbral shadow, which began at 8:25 PM!

It is clear from the details of the language

that I’ve highlighted in bold red font above that the September 2-3, 172 BCE

eclipse, proposed by John N. Stockwell (The Astronomical Journal, 1891, Vol. 11, pp. 5-6,)

also is not a

If we do the math, we’ll find that the

drifting of the seasons during those years, reckoning from the beginning of the

Roman calendar in the middle of the eighth century to the time of Caesar

Julius, was on the order of 0.113 days per year. For

the year 139 BCE (the most likely date for the Pydna lunar

eclipse being June 1-2, 139 BCE, which per my revised Olympiad calendar corresponds

to the 1st year of the 160th Olympiad [or else, but not likely, Sept

2-3, 153 BCE, which corresponds to the 3rd year of the 157th Olympiad! Cf.

Plutarch’s The Life of Aemilius 24.4

and Bill Thayer’s discussion

of the same (his last two paragraphs of footnote e)]) this corresponds to 753 BCE

– 139 BCE = 614 years, or 614 x 0.113 days = 69.4 days. That is, at a point

about 90 years (139 BCE – 49 BCE = 90 years) prior to my revised date for

Caesar Julius’ calendar reform, which reform, per Suetonius’ record required

a 15 months year for correcting the then extant migration of the seasons. Also,

Thoth 1 of the Egyptian calendar began on Sept 27, 139 BCE (and on Oct 4, 168

BCE.) Thus it is easy to see how that the shifting of the seasons were

affecting all of the calendars on both sides of the Mediterranean up until that

time.

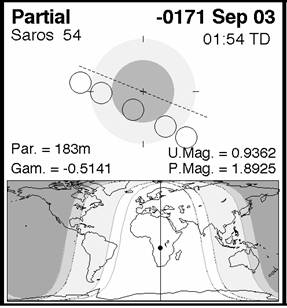

Above: The

lunar eclipses popularly attributed to the battle of Pydna.

Notice the

the U.Mag.=0.9362, i.e. 93.62% of the lunar diameter of the left map,

and the

map in the right picture showing where the eclipse was visible (cf. the large

picture below!)

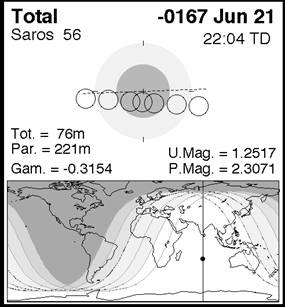

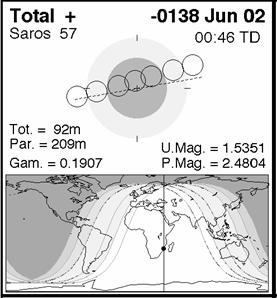

Above: The

eclipses of the battle at Pydna proposed by this author, in particular the one

to the right.

The

moving to

25° above the horizon before the eclipse concluded shortly after

The

remaining sliver of the September 3, 172 BCE partial lunar eclipse as seen from

Pydna, Greece at midnight and at the time of maximum eclipse.

Wrapping up the details of

Pericles eclipse

Now, let’s return to the Pericles eclipse and

402 BCE: In any given 40 day period there can be no more than one or two New

Moon events. Given also 1) that solar eclipses always occur at the exact time of

astronomical New moon, and 2) Plutarch’s words “In

the very beginning of summer the Peloponnesians and their

confederates… invaded Attica…,” we are faced with the conclusion that either

Pericles’ navy left at least a day or two, but possibly even a month or two,

prior to the arrival of the Peloponnesian invaders, or else they left, but not

likely, less than ten days before the forty days of the invading navy were up,

that is, less than 10 days before the Peloponnesians left Attica. Perhaps the

latter option might seem to be indicated by Plutarch’s words “left the

Peloponnesians still in Paralia…,” but considering all of the above

considerations, that certainly does not seem to agree with the language of

Plutarch and of Thucydides. Remember too, if the latter option were to be true,

then Pericles should have had considerable trouble with the plague among his

ship crew, and this should have been a major obstacle to their mission

objective, but no such thing is being mentioned. Thus we are left with the option

of Pericles and his navy leaving for their mission at least a day or two, and

possibly a month or two, prior to the invasion of the Peloponnesians.

Next, if indeed the words “In the very beginning of summer…” do follow the

day when “the

sun was eclipsed and darkness came on…” then we may also conclude

that the official calendar month Xanthikos began with the visible New

Moon on January 18, 402 BCE. For the year 402 BCE this corresponds to 753 BCE –

402 BCE = 351 years, or 351 x 0.113 days = 39.7 days shifting of the seasons.

Adding said 39.7 days, that is, the 40 days drift of the seasons, to January 18

we arrive at February 28 (beginning Feb 27,) that is, we arrive at the

beginning of the month, March, within which the spring equinox is expected in a

seasonally corrected calendar. This makes perfect sense, at least to me!

There remains one apparent major obstacle to

resolve: What about Thucydides’ words “in the afternoon happened an eclipse of

the sun,” that is, seeing that the solar eclipse of January 18, 402

BCE totally darkened the skies of Athens at 9:13± AM (08:18 UT + 1.5 hrs

= 9:48 AM local solar time) and not “in the afternoon” as suggested by the

above quoted translation. Well, as it turns out (cf. this word

study of mine!) the Greek words used by Thucydides

“μετὰ

μεσημβρίαν”

may also be translated “amidst the hot portion of the day.” That is, during

that time of the day when the sun was significantly hot, or say from

Thus, the astronomical hard facts of this

event must necessarily take precedence over words that, as in this case, may be

translated one way or the other.

Neither

one of the eclipses of Aug 3, 431 BCE and March 30, 433 BCE can be sustained by

the historical records of Plutarch and Thucydides when carefully considered

against the above referenced astronomical data. The correct date for the

Pericles solar eclipse can only be January 18, 402 BCE, which date, to the best

of my understanding of all the available facts is in total agreement with

all extant data as also considered in view of my revised chronology.

This placement of Pericles’ solar eclipse is

further sustained by my revised

placement of the battle at Pydna,

This result would not have been possible

without the direct guidance by and through the ultimate author of the Holy

Scriptures. Praise the Lord of Hosts!

Comments and donations

freely accepted at:

Tree of Life©

c/o General Delivery

Nora [near SE-713 01]

eMail: TreeOfLifeTime@gmail.com

…

…

The GateWays into Tree of Life Chronology Forums©

The GateWays of Entry into the Tree of Life Time

Chronology Touching upon the Book of Daniel©

Pearls & Mannah – “I found it!”

Feel free to use, and

for sharing freely with others, any of the truth and blessings belonging to God

alone. I retain all the copyrights to the within, such that no one may lawfully

restrain my use and my sharing of it with others. Including also all the errors

that remain. Please let only me know about those. I need to know in order to

correct them. Others don’t need to be focused upon the errors that belong to me

alone. Please respect that, and please do not hesitate to let me know of any

certain error that you find!

Without recourse. All

Rights Reserved. Tree of Life©